Australian general practice is under sustained administrative pressure. The average GP now spends hours each week completing documentation, managing Medicare requirements, and preparing care plans long after the waiting room has emptied. AI scribes have emerged as a promising solution, but most of the discussion, and many early tools have focused only on one part of the job: note-taking.

The reality is that transcription alone does not meaningfully shift the cognitive or administrative load inside a 10–15 minute consultation. Typing isn’t the bottleneck; the substantial administrative work that surrounds the consult is.

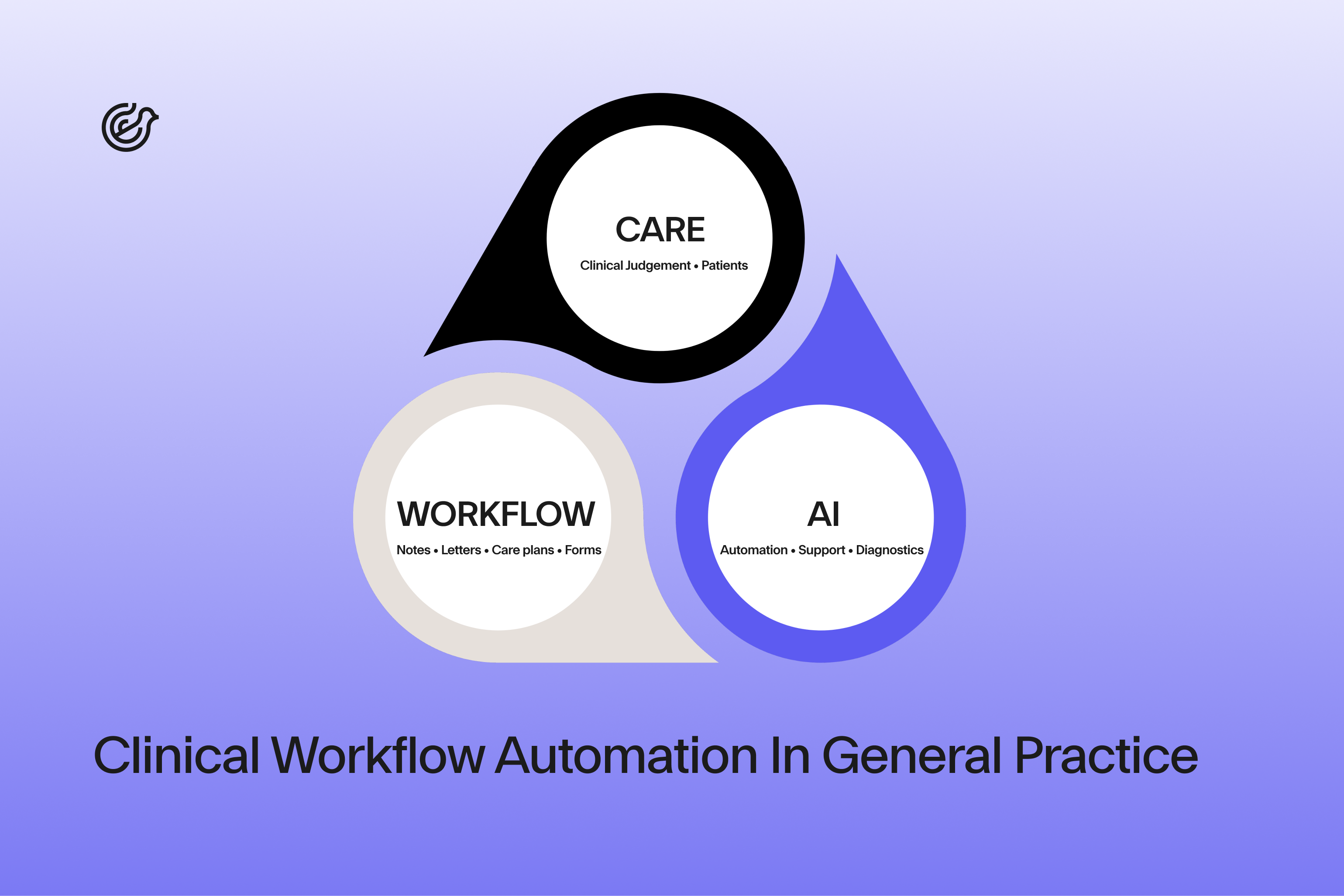

The next evolution of AI in general practice is not about generating longer notes. It’s about automating structured clinical workflows. These are the same workflows that drive Medicare claiming, continuity of care, chronic disease management, and medico-legal safety.

This is where ambient AI becomes less of a “scribe” and more of a clinical workflow partner.

Most GPs who have experimented with early scribes have learned two things quickly:

1. The note is rarely the problem.

The real burden sits in preparing MBS-aligned documentation, entering structured data, drafting summaries for care plans, and pulling information out of the EMR to populate templates.¹

2. Standalone tools can create as many risks as they remove.

Copy-paste transfers, offshore processing, unclear data provenance, and hallucinated diagnoses raise medico-legal questions. Recent NSW guidance explicitly warns that copy/paste in the EMR is widely used but can cause significant errors and medico-legal issues, and mandates local procedures to manage its use.²

GPs want help with:

And importantly: they want this help inside the software they already use, not in a separate window or through a clipboard.

A workflow partner extends far beyond summarising a consultation. It captures clinical content, organises it into structured fields, and uses that data to automate downstream tasks that currently cost GPs hours each week. This aligns with RACGP recommendations that CIS support structured data, standardised terminology and better usability for clinical decision support.³

Instead of producing a long blob of text, the AI identifies:

This structured data maps to fields already recognised in Australian practice software, particularly those aligned with AUCDI and SNOMED CT-AU in broader interoperability work.⁴

This is where the transformation happens.

Health Assessments (701/703/705/707/715):

AI can pre-populate established risk factors, screening responses, lifestyle findings, immunisation gaps, and safety-net items—reducing duplication and helping ensure documentation supports MBS expectations when audited.⁵

Chronic Disease Management Plans (721/723):

The workflow partner extracts goals, monitoring needs, allied health involvement, and measurable outcomes from the consultation and maps them into the CDMP/TCA structure for GP review.

Mental Health Treatment Plans (2715/2717):

Symptom history, risks, functional impairment, psychosocial stressors, and discussed preliminary goals can be drafted in real time. If DASS-21 or similar tools are used, the scores can be captured and summarised.

A true workflow partner can support:

This is why the market is now shifting from “AI transcription” to workflow automation aligned with RACGP Clinical Information System (CIS) expectations and electronic Clinical Decision Support (eCDS) principles.⁶

Standalone tools simply cannot automate clinical workflows safely and reliably.

Deep integration allows:

These tasks currently rely heavily on GP memory or manual workflow steps—creating omission risks.

Based on the clinical conversation, AI can:

A 715 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Assessment, for example, contains multiple sections that can be partially completed in-consult—dramatically reducing after-hours time. Current item descriptors and requirements should always be cross-checked against MBS Online as they change over time.

Here the benefit compounds.

Based on the clinical interaction, AI can pre-fill:

From the consult, AI can assist with:

This allows GPs to spend more of the consult on connection and assessment, not typing.

Before:

A GP spends 25–30 minutes after morning clinic completing a CDMP and a 2715 from two earlier consults. Notes must be re-read, goals rewritten, and medication lists checked manually.

After:

During the consult, the AI extracts relevant history from the conversation and auto-populates the CDMP and MHTP scaffolds.

The GP edits in real time and prints or uploads immediately.

No backlog. No recreating the consult hours later.

The rise of AI scribes has coincided with increasing regulatory scrutiny. In 2025, both the TGA and professional bodies highlighted digital scribes and AI documentation tools as an area of focus, particularly where software moves beyond transcription into diagnostic or treatment suggestions.⁷

This isn’t to limit innovation, it’s to protect patient safety.

Under the Privacy Act and associated guidance:

Redaction does not fully remove re-identification risk; even a medication brand or unique phrase can expose identity.

GPs should confirm:

Medical defence organisations such as MIPS (Medical Indemnity Protection Society) (ref) and MDA National (ref) have consistently highlighted that documentation practices which rely heavily on copy-forward, templated text or unverified transfers can introduce inaccuracies into the clinical record and increase medico-legal risk.¹¹,¹²

Common risks include:

For this reason, safer system design increasingly favours direct integration into the clinical information system, clear audit trails, and workflows that support real-time review and clinician sign-off, rather than manual copy/paste processes.

Recent guidance from RACGP and TGA distinguishes between:

GPs remain responsible for:

Any tool that generates diagnostic or therapeutic suggestions without transparent guideline linkage should be treated with caution.

A safe system should have:

Emerging guidance from professional and safety bodies including the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP) and the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (ACSQHC), increasingly emphasises the importance of local clinical governance, transparency, and human oversight when using AI tools in practice.⁹

Well-designed AI can strengthen medico-legal defensibility by improving:

But poor design can create new risks:

The safest pathway is simple:

AI drafts - GP reviews and edits - GP owns the record.

Early adopters—particularly high-volume practices and registrars—have demonstrated a few common patterns.

These offer the clearest reductions in admin load.

Successful practices often nominate:

This mirrors broader guidance to treat AI tools like any other clinical system, with defined roles, policies and review cycles.¹⁰

Useful metrics include:

Before:

A registrar new to Australian Medicare workflows spends evenings completing CDMPs and 2715s from earlier consults. Notes are revisited, requirements double-checked, and plans pieced together after the clinical context has faded.

After:

During the consult, the AI software captures key history and auto-scaffolds the CDMP and MHTP.

The registrar reviews in real time, with supervisors focusing on clinical reasoning rather than paperwork.

Less after-hours work. Clearer documentation. Better learning.

Ask:

Confirm:

Require:

Ask vendors:

Look for alignment with:

These standards help future-proof your data for evolving digital health initiatives and eCDS frameworks.

A straightforward adoption roadmap:

General practice doesn’t need longer notes. It needs faster, safer, more structured workflows that reflect how GPs actually deliver care under Medicare and emerging AI safety expectations.

The next evolution of AI scribes:

The real promise of AI scribes is not automation; it’s liberation. When ambient AI takes on the administrative and workflow load, the GP is freed to return to the highest-value parts of the job: clinical reasoning, patient rapport and shared decisions that improve outcomes. But this only works when AI stays in its lane: documentation, structure and workflow while maintaining privacy, security and safety; not diagnosis.

The outcome depends on decisions being made right now: which tools the profession chooses, how they integrate with practice software, and whether they strengthen or weaken the clinical record. Systems built for Australian workflows, safety and Medicare requirements can genuinely elevate the craft of general practice.

If you’d like to see how a workflow-driven approach changes day-to-day practice, you can trial Lyrebird directly inside Best Practice and measure the impact on care plans, health assessments and after-hours admin.

Sign up and start a free trial to Lyrebird Health’s AI medical scribe.

References:

1. Australian Government Department of Health. Administrative record keeping guidelines for health professionals. Canberra: Department of Health; 2021. Available from:

https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2021/06/administrative-record-keeping-guidelines-for-health-professionals.pdf

2. South Eastern Sydney Local Health District. Electronic Medical Record (eMR): Copy and pasting within electronic documentation – SESLHDPR/605. Sydney: NSW Health; 2020. Available from:

https://www.seslhd.health.nsw.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/SESLHDPR%20605%20eMR%20-%20Copy%20and%20Pasting%20within%20Electronic%20Documentation_0.pdf

3. Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Minimum requirements for general practice clinical information systems. East Melbourne: RACGP; 2023. Available from:

https://www.racgp.org.au/FSDEDEV/media/documents/Running%20a%20practice/Support%20and%20tools/Minimum-requirements-for-general-practice-CIS.pdf

4. Therapeutic Goods Administration. Digital scribes and clinical documentation software. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care; 2024. Available from:

https://www.tga.gov.au/products/medical-devices/software-and-artificial-intelligence/manufacturing/artificial-intelligence-ai-and-medical-device-software/digital-scribes

5. Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) Online. Canberra: Australian Government; 2024. Available from:

https://www.mbsonline.gov.au

6. Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Clinical information systems and electronic clinical decision support. East Melbourne: RACGP; 2023. Available from:

https://www.racgp.org.au/advocacy/advocacy-resources/minimum-requirements-for-cis

7. Therapeutic Goods Administration. New information on digital scribes. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care; 2025. Available from:

https://www.tga.gov.au/news/news-articles/new-information-digital-scribes

8. Australian Government Department of Home Affairs. Privacy, data security and digital health guidance (RACGP reference document). Canberra: Australian Government; 2022. Available from:

https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/files/national-data-security-action-plan/royal-australian-college-of-general-practitioners.pdf

9. Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. Artificial intelligence in healthcare. Sydney: ACSQHC; 2023. Available from:

https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/our-work/e-health-safety/artificial-intelligence

10. Australian General Practice Accreditation Limited. Artificial intelligence in general practice: industry guidance for safe and smart use. Sydney: AGPAL; 2024. Available from:

https://www.agpal.com.au/news/artificial-intelligence-in-general-practice-industry-guidance-for-safe-and-smart-use/

11. Medical Defence Organisation (MDA National). Artificial intelligence and clinical documentation: medico-legal considerations. Adelaide: MDA National; 2023.

12. Medical Indemnity Protection Society (MIPS). Artificial intelligence tools in clinical practice. Melbourne: MIPS; 2023.